About

I am your author and would like to share with you what motivated me to write about Tibet and subjects related to the Art of War.

It may have been sheer coincidence that I was commissioned as an officer in the Indian Army in December 1959, exactly nine months after the Fourteenth Dalai Lama arrived in the Kameng Division of Arunachal Pradesh seeking exile. The forcible occupation of Tibet by China in 1950-51 was one of the most tragic events of the twentieth century, an event to which the world, surprisingly, remained largely oblivious. Tibet’s demise was orchestrated by the nations that had once taken advantage of its weaknesses—rooted in its theocratic regime—and exploited it under the pretence of protecting its sovereignty, which adds to the tragedy.

In 1962, I found myself in Sikkim as part of the 17th Infantry Division, facing the PLA at Nathu La Pass. My curiosity about how the relationship between India and China had deteriorated from “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” in 1954 to bitter animosity by 1959 grew stronger, but I could not find any satisfactory answers. I neither found any books on the history of Tibet nor met any scholars who could enlighten me. Among the least informed, perhaps, were the officers of the armed forces. Their knowledge of Tibet’s history was limited to a vague familiarity with Captain Younghusband’s military expedition to Tibet in 1903-1904, an expedition meant to “teach Tibet a lesson” for its defiance of allowing a British embassy to meet the Dalai Lama. The expedition consisted primarily of Indian soldiers.

For us, the image of Captain Younghusband was that of a hero—galloping ahead of his force on a highbred charger, wielding a shining sword, and chasing down Tibetan marauders. He was the hero we thought we should emulate. Alas, when I learned the reality—that the expedition led to the massacre of practically unarmed Tibetan militia and forced an illegal treaty on Tibet, in the absence of the Dalai Lama, turning Tibet into a British fiefdom—I was filled with deep anguish and shame for considering Younghusband a hero.

I was a participant in the debacle of the India-China War of 1962. No gainsaying that it left the Indian armed forces demoralised and ashamed. Unfortunately, we received no word from the military brass about the causes of the failure. In the vacuum, gossip-mongers had a heyday and several rumours from wild to weird went around unabated. Instead of burying highly damaging rumours by providing authentic information, the leadership of the country decided to brush it under the carpet, causing greater damage to the image of the armed forces. The PLA under Mau Zedong launched a well-conceived, planned and finely orchestrated campaign with close to eight divisions against badly equipped and trained close to five infantry brigades. Besides the Indian Armed Forces’s performance during the India-Pakistan War of 1965 was lacklustre, notwithstanding its overall superiority over Pakistan.

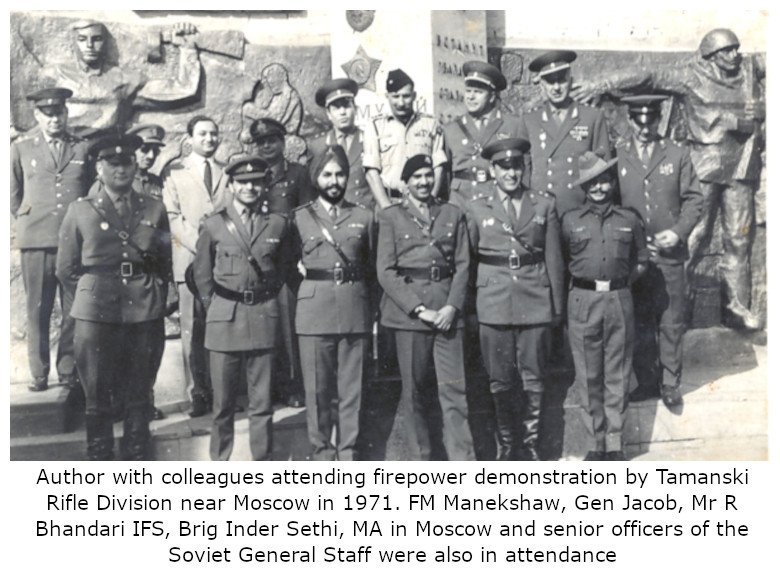

Strangely, once again no effort was made to analyse the war in depth to reveal failings and their causes to carry out remedial measures. In 1971 India once again went to war against Pakistan. It was an all-out war in which all the services took part. The war was a success from a political point of view and resulted in the liberation of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. However, militarily it was inconclusive like all its other wars.

In 1966, following the 1965 Indo-Pak War, an Indian military delegation visited the Soviet Union. Among the delegation members was General P.P. Kumaramangalam. During negotiations, the Soviet government agreed to train four Indian Army officers at the prestigious Frunze Military Academy. This marked the first time that the USSR opened the doors of its renowned academy to officers from a nation outside the Warsaw Pact or those militarily aligned with the Soviet bloc.

The primary objective of sending these four officers for the four-year training program was to gain an in-depth understanding of Soviet warfare, particularly in the realm of operational art—an area where the Indian armed forces had limited knowledge. Upon their return in 1972, however, these officers were deeply disappointed to find that their expertise was not being utilized by the Indian Army. As a result, the Indian military continued to conduct operational-level wars using tactical principles.

The distinction between tactics and operational art might be perplexing to some readers. Traditionally, warfare was divided into two categories: strategy and tactics. However, in the early 19th century, revolutionary changes in warfare—such as advances in technology, mobility, the structure of armed forces, and the development of mass armies—created a significant gap between tactics and strategy. This gap could not be addressed by either tactics or strategy alone.

After extensive scientific research, the Soviets developed the concept of “Operational Art,” which served as a bridge between strategy and tactics. They outlined its principles and effectively employed the concept during World War II, as did the Germans. Although the U.S. Army was aware of operational art, it only officially recognized the concept in the early 1980s, after which it was adopted by other military powers.

Unfortunately, the Indian Armed Forces have not fully embraced the concept of operational art and continue to rely on tactical principles to conduct operational-level wars. Without a coherent, well-articulated, and pragmatic military doctrine, no war can be won.

Having been unable to convey the importance of operational art and the development of its doctrine to win future wars, I decided to document my knowledge on the subject for posterity. The reasons for delaying the publication of these books for nearly three decades are explained in the first few pages.